I should have published this a year ago, but life has a way of burying you. This is a project that I completed last year for my friend and antique sword collector, Lee Jones. Lee is a retired pathologist who has been collecting antique swords and weapons for a good portion of his adult life. Lee was friends with Ewart Oakeshott and many of the other major collectors of swords and weapons. Lee’s private collection is arguably one of the finest ancient sword collections in the United States.

I should have published this a year ago, but life has a way of burying you. This is a project that I completed last year for my friend and antique sword collector, Lee Jones. Lee is a retired pathologist who has been collecting antique swords and weapons for a good portion of his adult life. Lee was friends with Ewart Oakeshott and many of the other major collectors of swords and weapons. Lee’s private collection is arguably one of the finest ancient sword collections in the United States.

During the fall of 2016, I had the privilege of joining swordsmiths Peter Johnsson and Kevin Cashen at Lee’s house to document swords from his collection. Lee was a gracious host. We enjoyed several evenings listening to Lee tell the stories of how he collected many of the outstanding items in his collection. Of course, he allowed us to handle and document a group of amazing swords in his collection. A wonderful Alexandria arsenal sword and an amazing Ulfbert were just two of the highlights. Lee also showed us a number of axes and other weapons in his collection.

At one point, Lee brought out this tiny axe, and explained that it was in the tomb of a Viking boy. It was found with a small sword, shield boss, and spearhead. The axe was very corroded, but there was something charming about. It had an alluring presence about it. Perhaps it was because it spoke volumes about the love of a father for a son who had departed too early. Whatever the reason, I was drawn to it. I spent the good part of an hour documenting the small axe. During the last day of our stay, Lee asked me if I would be interested in making a reproduction of the axe for his private collection. I was honored, and of course, I said “yes.”

This axe is mentioned in Ian Pierce’s book, Swords of the Viking Age, on page 86 in the caption of the picture of the boy’s sword. The axe, as well as the sword, spearhead, and shield boss, were found in Ringebu, Oppland, Norway.

I asked Lee if he would provide some information on how he acquired the axe. Here is the story:

This diminutive Viking style axehead came most recently from the extensive antique European arms and armor collection of Howard M. Curtis, athlete and noted Hollywood stuntman. First coming to wide notice in the television series Ripcord, Mr. Curtis’ film career ran from 1957 until his untimely death in 1979 when during a benefit skydiving demonstration he attempted to save an amateur skydiver whose lines became entangled and who then panicked, leading to a free fall death for both men.

This diminutive Viking style axehead came most recently from the extensive antique European arms and armor collection of Howard M. Curtis, athlete and noted Hollywood stuntman. First coming to wide notice in the television series Ripcord, Mr. Curtis’ film career ran from 1957 until his untimely death in 1979 when during a benefit skydiving demonstration he attempted to save an amateur skydiver whose lines became entangled and who then panicked, leading to a free fall death for both men.

Mr. Curtis’ extensive collection and supporting specialized library came to a single-owner sale at Christie’s in London in the fall of 1984. This axehead was one in a lot of eight items (#144), incidental to a Merovingian francisca head. Shortly thereafter the specialist dealer who had managed my purchases at that auction was contacted by another of his clients about the small axehead. This collector had acquired the same axehead, along with a similarly small sword in the late 1960s and the sword, this axehead, a small spearhead, arrowheads, a shield boss and cloak pin – all of similarly reduced proportions – were reported to have been found in the late 19th century in a boy’s weapon burial at Ringebu, Norway.

Following Mr. Curtis’ death this collector, from whom the axe head and sword had previously passed to Mr. Curtis, had contacted the family about reacquiring the items. He was successful in reclaiming the sword, but the axe head could not be found within Mr. Curtis’ extensive collection at that time and it eventually ended up at Christie’s. The collector later rediscovered the spearhead and facilitated its reunification with the sword and axe head, but the fate and location of the other items in the group remains unknown.

Since the axe was heavily corroded, I had to make an educated guess as to the original shape. I sketched the axe out then made a drawing in Illustrator that would serve as my guide for the reproduction. I forged the axe slightly large, so that I could grind and file it to the final dimensions on the drawing. In the picture below (R), you can see a black line around the perimeter of the head that represents the axes final dimension after grinding and filing.

I utilized refined, 19th century wrought iron that was from links in an anchor chain. I wanted the body to have clear slag lines to give it the appearance of ancient iron. The iron had very nice slags lines that formed a pleasing random pattern on the axe body once it was etched. The bit was forge welded into the body and is 1080 high carbon steel.

Around the same time I was making this axe, I was experimenting with ebonizing oak to give it a bog oak appearance. The haft on this axe is a piece of oak that I ebonized while I was experimenting with the process. Here is a link to my blog explaining the process.

Overall, I am very pleased with the result. It is always a guessing game when you are reproducing an artifact that is corroded, but I feel that I was able to stay true to the original shape of the piece. The 19th century iron and ebonized haft combine to make a convincing reproduction. When I shipped the axe to Lee, I received this lovely email explaining his react to the axe.

Dear Eric,

The axe arrived in perfect order this afternoon, obviously very well packaged to prevent damage to either the delivery man or to the axe. I was immediately and unexpectedly struck by just how well it felt in the hand – what a terror a ten year old might become with this in one hand. In old India there were some axes with heads almost this small that were clearly formed for function as adult’s weapons. Anyway, I can surely see why you have gained such a reputation for making fine classical axes. The etched, patterned body is most impressive and is made even more so by the contrast to the brightly polished inserted edge. I especially like that. The shaping and finish of the haft are superb and I am really enjoying seeing and feeling how different the whole of the weapon is when compared with the rusted remains of the head alone.

The next time I have the right light and am set up for photography I will take some photographs of your recreation along with the original group of artifacts and send them along to you. It is nice to make the comparison with what the rusted axe might have looked like a thousand years ago, though I am confident that it was never quite as nice as the axe you have made. I thank you for your thoughtful kindness…

Many thanks and very best regards… Lee

Gallery of Photos:

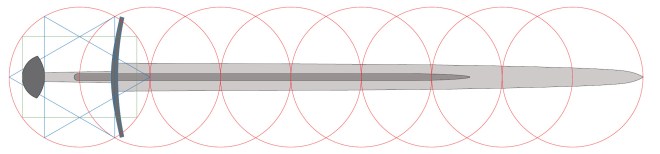

This project is a custom recreation of an early medieval sword with basic specifications by the customer. Similar swords saw use in the late 10th century to the mid 11th century. The blade is forged 80CRV2 high carbon steel. Fittings are forged mild steel. The scabbard and grip are dyed a pleasing burgundy red. The blade can be classified as a Geibig 6, but there is always some ambiguity when typing these swords. The scabbard is thin wood layers that were glued together to form a core. The core was then covered in leather and stitched on the back side. The laced scabbard belt is dyed black. This type of belt was a common style used by the Normans (and others) during this period.

This project is a custom recreation of an early medieval sword with basic specifications by the customer. Similar swords saw use in the late 10th century to the mid 11th century. The blade is forged 80CRV2 high carbon steel. Fittings are forged mild steel. The scabbard and grip are dyed a pleasing burgundy red. The blade can be classified as a Geibig 6, but there is always some ambiguity when typing these swords. The scabbard is thin wood layers that were glued together to form a core. The core was then covered in leather and stitched on the back side. The laced scabbard belt is dyed black. This type of belt was a common style used by the Normans (and others) during this period. While I firmly believe there is nothing magical or mystical in these principles, I believe that these geometric strategies help to create designs that are pleasing to the human eye. There are shapes and proportions that strike a chord with us. Perhaps this is one reason these principles were used by master of various crafts throughout history.

While I firmly believe there is nothing magical or mystical in these principles, I believe that these geometric strategies help to create designs that are pleasing to the human eye. There are shapes and proportions that strike a chord with us. Perhaps this is one reason these principles were used by master of various crafts throughout history.

This is the final axe in a series of three hand forged, single-hand war axes I’ve been finishing. Like the previous two axes, this axe is patterned after the many examples of late 10th to early 11th century single-hand war axes. This type of axe was an agile yet brutal weapon that would have been a common choice for a soldier fighting in close quarters or in a shield wall.

This is the final axe in a series of three hand forged, single-hand war axes I’ve been finishing. Like the previous two axes, this axe is patterned after the many examples of late 10th to early 11th century single-hand war axes. This type of axe was an agile yet brutal weapon that would have been a common choice for a soldier fighting in close quarters or in a shield wall.

This axe features a 1018 low-carbon steel body and eye socket and a 1080 high-carbon steel bit. The body and eye were drawn out like a “bow tie.” The two sides were forge welded together to form the body. The eye was further refined by forging over a steel mandrel to arrive at the desired socket shape.

This axe features a 1018 low-carbon steel body and eye socket and a 1080 high-carbon steel bit. The body and eye were drawn out like a “bow tie.” The two sides were forge welded together to form the body. The eye was further refined by forging over a steel mandrel to arrive at the desired socket shape.